I've been away for a while! It’s not because I'm spending too much time scrolling on my phone; it's actually because I've been using all of my technology to bring to a conclusion one of the biggest projects I've had in the last few years, which is finally coming to fruition…

The book is Reboot: Reclaiming Your Life in a Tech Obsessed World, and it's out on the 31st of August.

For this edition of Your Life on Tech, I wanted to do something a little bit different. I transcribed this from a completely extemporaneously recording with no text in front of me, I had no script (scary), but I wanted to tell you a little bit about what Reboot is, about how I came to write it, why I came to write it, and what I'm hoping that it's going to be able to do for its readers, as it did for me.

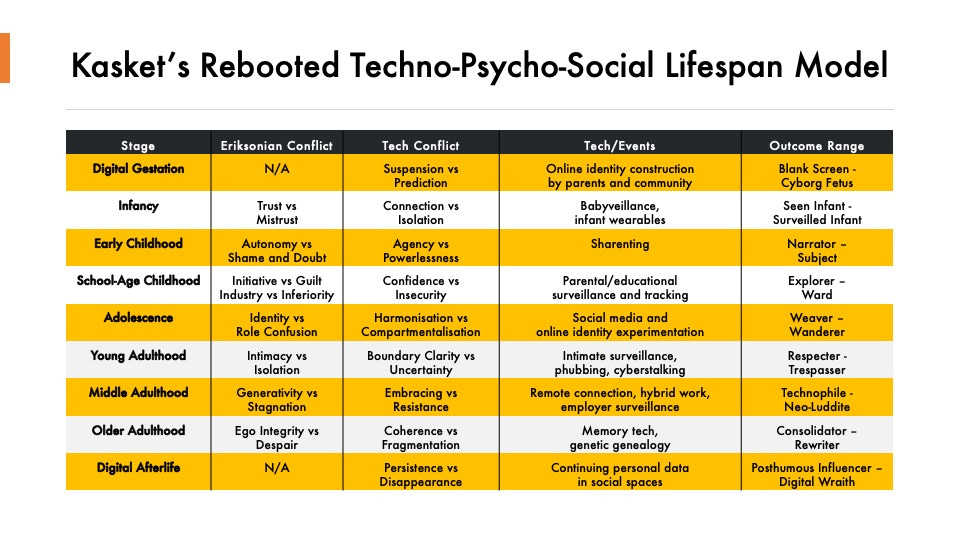

When I was writing my previous book, which was about death and the digital age, it ended up — towards the end of the book — in a place that I didn't expect. I had started talking about what happens to your data at the end of your life, but in one of the latter chapters for that book, I started talking about what happens with your data at the very beginning of life. I started to think in fact about my own child and how I had contributed significantly to our digital footprint from the very earliest moments of her life, even before she was born. I had already substantially affected not just her ultimate digital legacy, her digital footprint that one day she would die leaving behind, but I also had shaped her personality and her experience of the world — more powerfully, I think, than parents in a pre-digital era would've been able to.

And so, when I was sitting in a meeting about something else at my publishers with my literary agent, I happened to mention this idea. I said to my agent, I wonder if the life stages — the psychological and the social life stages of the human lifespan, as we've always conceptualised them in Psychology 101 — I wonder if they're different now with technology stirred in.

We went on to talk about other things, but as we walked onto the street together and my agent grasped my arm and said, oh my God. I had no idea what she was talking about, but he was talking about this idea for this book that I'd accidentally mentioned in this meeting.

It took me a considerable period beyond that moment for me to be thinking oh my God about this concept.

As with a lot of authors when they have an initial idea, I didn't really know where to start. I simply knew that I wanted to write a book that would help people be more balanced in their approach to the technology in their lives. I didn't want to write another digital detox book or an unrealistic, un-pragmatic book about how we should all put down our devices or use this less or that less. I didn't really feel like that kind of approach has helped me, and I haven't really seen it help a whole lot of other people. These ‘shoulds’ about what we ought to do with our technology usually focus on how much we need to reduce it or put it to the side.

I wanted something that was different, more flexible, more individual — something that would help people think about tech and their own lives, what was serving them well and what was serving them not so well. But again, like I say, it was hard to know where to start.

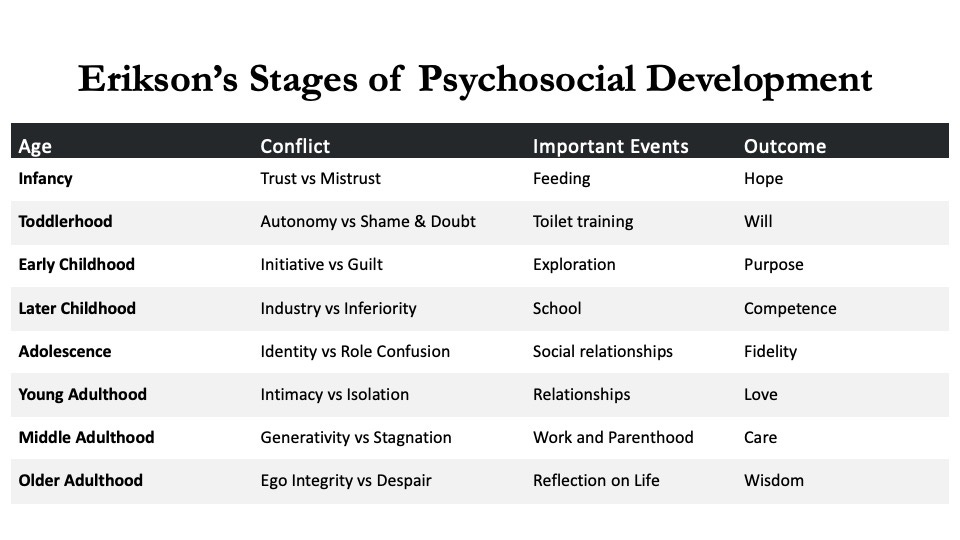

And then I remember writing an essay in my undergraduate studies at Indiana University Bloomington about the famous psychologist of identity, Erik Erickson, who developed his model back in the 1950s.

I wrote an essay about Erikson, and I have no idea how I did it. By that I mean that I literally don't know how research was possible in the late 1980s. I remember it vaguely. I know that I did it in the library, because there was no other option for accessing information. I remember being stuck into the card catalogs, which were my search engine at the time. I remember very strong sense memories of them revolving around touch, how these long drawers of cards felt underneath my fingers. And the books for the core texts that everybody had to use for their classes in psychology and sociology were worn away and dirty on the edges. Erik Erikson's books, especially about his books about identity were the ones that were dirty on the edges in that section of the card catalog.

And when I think about my internet-free psychology studies, my mind also jumps to other areas of life as it felt back then, and things were so extraordinarily different. As an emergent adult, for example, I visited the American Express office in each major city that I visited — Munich, Paris, et cetera — and I had to ask if I had any post from home. I know that my parents would've absolutely loved confirmation on the daily that I was still alive, but it just wasn't practical because I was operating at that time on 30 American dollars a day for everything, and I didn’t have spare change for payphones. I wrote traveler's checks. I consulted actual paper atlases. If I met somebody on my travels and I happened to lose their name and address where I'd written it down, I knew for sure that I would never speak to them ever again. I shot several roles of film, and that seemed like an awful lot, and probably I still have the negatives somewhere.

But I describe these ancient wonders of the world to my kid, and she looks at me like I'm an oddball, an alien from another planet, and I am, I am an alien from another planet. She's not entirely wrong — because there's a world of difference between Generation X and Generation Alpha, which my kid is. She views me as clueless about how things are today, but she's not quite right about that because I have been keeping Eric Erikson's model in my mind — along with a lot of my other pre-digital era psychology theories and ideas — keeping those alive in my practice and with my psychotherapy clients. And I think a lot too about the intersection between psychology and 21st-century technology.

So now, for this book I wanted to consider whether Erik Erikson's map of the human lifespan still applies today. How much has changed, I wanted to know, in the space of a couple generations?

I had both personal and professional motivations for writing Reboot, because I am in Erik Erikson's middle-adulthood stage. He called it Generativity versus Stagnation. Midlifers can either keep pursuing their ambitions and their goals, or they can get stuck. This developmentally normal crisis took on a really abnormal scale for me during the Covid 19 lockdowns. All of my work shifted online — it's still online for the most part. Most of my socialising shifted online. I probably wouldn't have generated this book if I hadn't been so anxious to avoid what felt like a double stagnation of turning 50 and pandemic lockdowns.

I was also struck by how many of my psychotherapy clients have dilemmas and troubles that are now relating to technology. Think about your own difficulties in the world and your relationships with and through tech.

People feel addicted to or fatigued by their screens, and parents are stressing over their kids growing up digital.

People who are romantic partners or former romantic partners snoop on each other when they're feeling insecure.

There are employees that come to see me that are upset about the productivity monitoring and all of the metrics at work. Or, especially lately, worried about AI rendering their jobs obsolete.

People have things about their identity and things about their narratives unearthed via commercial genetic testing, things that they never expected that challenge their life autobiographies.

And, like I've been writing about for a couple of decades, people who have lost someone feel traumatised by either losing access to somebody's digital remains, or traumatised by accessing a little bit too much of those digital remains.

So Reboot is about the whole of our lifespan, about the fact that tech has become both the mediator and the middleman in nearly every relationship we have in modern life. And we have a relationship with technology itself. Technology is cast in a role in a lot of our very human dramas. It's a player in those dramas!

And we are constantly making decisions about our data, about other people's data, about devices. Those decisions don't just affect us. They affect other people, and often those other people are the people that are nearest and dearest to us. We get ensnared by our digital habits. We can't seem to wriggle free.

We find ourselves talking and acting, behaving in particular ways about all of this tech that surrounds us, maybe especially when it's unfamiliar tech that scares us a little bit or disrupts us in some way. But we fall into speaking about ourselves as victims and about technology, whether that's our devices or the big tech companies behind them as our persecutors.

Or we look at technology to rescue us from our problems, whether those problems are boredom or dissatisfaction in our relationships, or other things that we're avoiding. And so we are the victims. Technology might be our persecutor, it might be our rescuer, or we looked to technology to rescue us from one thing and find ourselves, as an unintended consequence, maybe persecuting someone else. Maybe it's our kid. Maybe it's our employee. Maybe it's partner or former partner. Maybe they know that they're being persecuted by us or disadvantaged by us, and maybe they don't — it has really wide ranging individual and social effects.

So the whole point of Reboot is to ask and answer the question of: are we as passive and victimised as we assume?

I want to believe — and I'm presenting the case to people in Reboot — that technology of course influences us. Of course it influences our relationships. But it doesn't determine us. And when we believe that tech has some kind of monolithic impact on us, that it's unilaterally shaping us and our choices and our behaviors, of course, you're gonna feel powerless. Of course, you're going to feel like tech, and not you, is in the driver's seat. Reboot, I hope, is a way for people to reclaim the fuller extent of their agency and power, agency and power that we've had all the way along, but we've kind of fused with the script that we don't have it anymore, that we haven't got access to it anymore, that there's nothing we can do and everything is racing ahead of us technologically in the world, and we are its victims.

Don't get me wrong, there's still a whole lot of problems out there. There's things that I'm concerned about as much as you're concerned about them, but I want to make sure that I'm always acknowledging and applying the leverage that I have where it most matters. And Reboot is an exercise in helping you figure out what those points of leverage are for you and whether you want to pull those levers.

So I'm really, really, really excited to be sharing Reboot with you all. Now, a couple of different things. Number one, if you're listening to or reading this, you may or may not be a subscriber to this newsletter. However, you could be — if you wanted to be — either a free subscriber or a paid subscriber.

If you decide to be an annual paid subscriber to this podcast or to my other podcast, which is called Wednesday's Ghost, which is a storytelling podcast, you'll actually get a free copy of Reboot when it's released on the 31st of August, as well as a copy, if you wish it of my previous book, All the Ghosts in the Machine, which is an examination of what happens to your data when you die, but beyond that, that's used as a lens to understand much more about our digital lives, including issues of power and control in the big tech/big data era.

That's one option for you. Another option — and I did not realise this until really recently — who knew all the stuff that I'm finding out about the publishing process — pre-orders are really important for authors. They're important for books, and for the reach and the spread of books with great ideas. Pre-orders determine how many copies of a book a bookstore orders in, whether they choose to stick that book in the window. It determines whether or how books climb the bestseller list, and as a consequence, how many people are going to get access to that book and realise that it's out there and get interested in it.

So the very best way of supporting an author that you like or ideas that you care about is by pre-ordering that author's book.

If you're in the UK you can go ahead and do that now.

We’re still working on some distribution and publication deals for other territories, but certainly in the UK you can go onto amazon.co.uk, or your local library, or your local independent, or your local Waterstones and say, I would like to pre-order a copy of Elaine Kasket's Reboot, please. They’ll more than happily do that for you.

As the 31st of August approaches, there's going to be a set of 10 podcast episodes for Your Life on Tech, and they’re going to be interview-related podcasts, dialogues with some of the great folks that I talked to for the book, as well as some of the people that I didn't get a chance to chat with, but I'm really happy to loop in now.

I want to thank you a lot for listening to or reading Your Life on Tech today. I appreciate it so much, and I cannot wait to share these ideas with you!